“It was meet that we should make merry, and be glad: for this thy brother was dead, and is alive again; and was lost, and is found.” -Luke 15:32

Zombies have had a good run as cultural metaphors, from George Romero’s 1978 zombie flick, Dawn of the Dead, which is set in a shopping mall, to Simon Pegg’s Shaun of the Dead, whose title sequence suggests that we’re all already zombies, anyway, so what’s the problem?

Well, vampires are having their time in the sun, thanks to Ryan Coogler’s 2025 hit, Sinners. Ostensibly based on the myth of blues legend Robert Johnson meeting the devil at a Mississippi crossroads, Sinners is also a dark retelling of the story of the Prodigal Son, a theme that Coogler explored in one of his earlier films, Black Panther. This time, instead of the diasporan Killmonger returning to the Mother country to wreak havoc, we have two brothers (both played by Michael B. Jordan, who also playsed Killmonger) returning from Chicago—a popular destination of the first Great Migration—to the deep South in 1931.

The film’s summary at the Internet Movie Database reads, “Trying to leave their troubled lives behind, twin brothers return to their hometown to start again, only to discover that an even greater evil is waiting to welcome them back.” But that’s incorrect; the brothers are bringing trouble with them. On purpose. Sporting gold teeth and fancy suits, flush with cash from some obscure source, they spend the first part of the film starting up a juke joint and, not inviting, exactly, but luring the towns people. There is an unmistakable whiff of the devil about these two, accurately named “Smoke” and “Stack.” One of them even appears frequently wreathed in smoke.

Not everyone, of course, is “invited to the cookout,” but it’s interesting to see who is: sharecroppers, musicians, past lovers, a half-White siren named Mary. (As one of the characters later explains, “She’s here because she’s family.”) There’s also an Asian couple, which expands the boundaries of the protected community to reference, not only the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, but also our current political situation with immigration.

The vampires in the film don’t simply show up at the juke joint; they’re summoned by the guitar that Smoke/Stack give(s) to a young blues musician named Sammie. The film thereafter plays on the familiar trope that a vampire cannot enter your house without being invited. But vampires, of course, are particularly adept at getting in, a talent displayed when the head vampire, Remmick, tries to talk his way past the bouncer. There’s a certain whiny pathos to his argument—a sort of riff on the vapid entreaties of “All Lives Matter”—and he points to the inclusion of Mary, the only character with a foot in both worlds, and the first one to break the force field.

The real threat to the dwindling number of survivors inside the juke joint is not death, which is presented as a transition of grace and beauty, but forced assimilation. In that respect, it mirrors another American horror film, Jordan Peele’s Get Out. The vampires share thoughts, like the Borg in Star Trek, and—what’s worse—they share physicality. Perhaps the most unsettling moment in the film comes when assimilated denizens of the juke joint are forced to join the three White hillbillies in a blood-drenched Irish jig, a sort of perverted version of “Thriller,” but with colonialist undertones. It’s not just horrifying—it’s cruel.

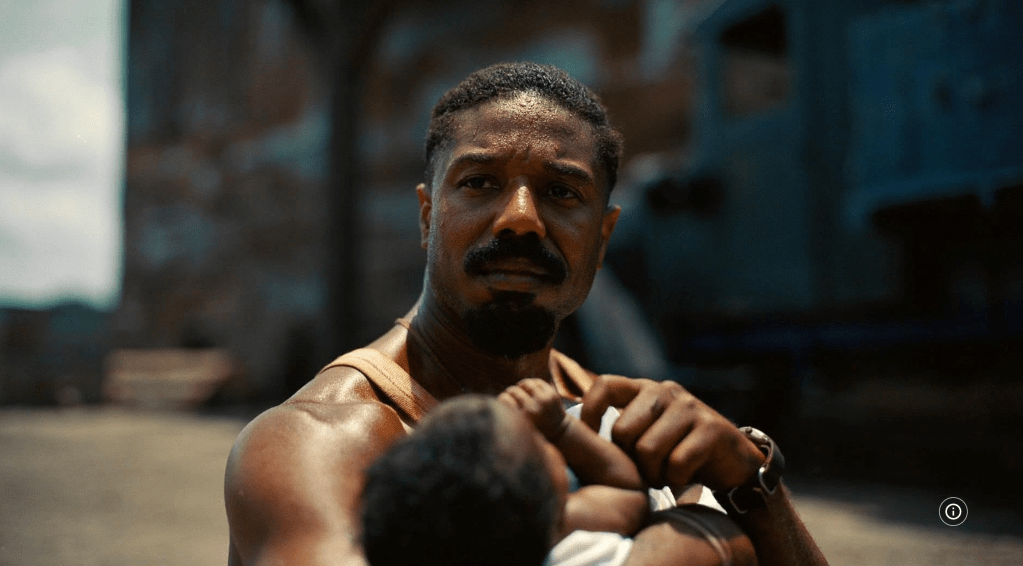

The movie is visually stylistic. Characters are almost always placed dead center, looking toward—but not at—the viewer:

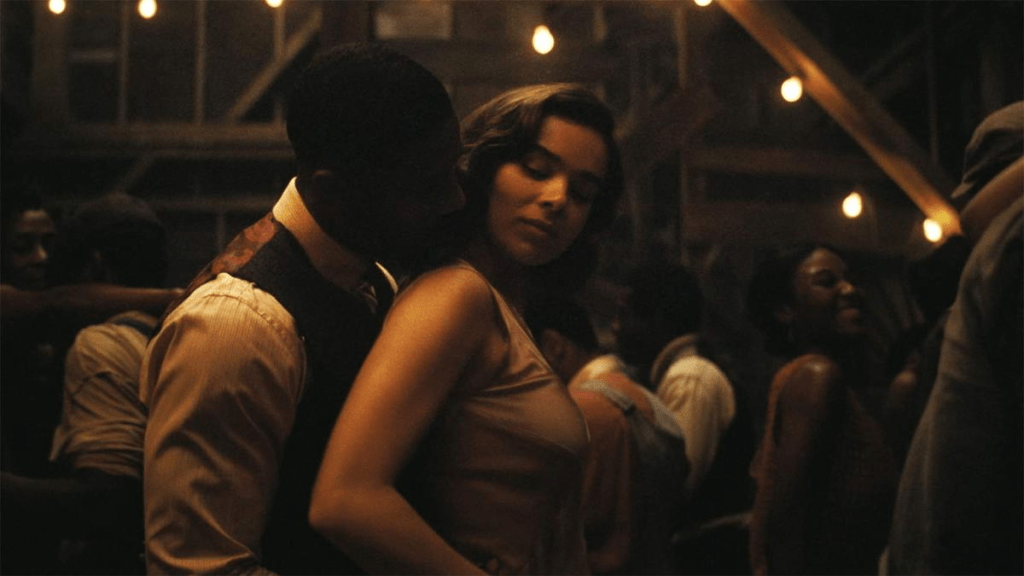

The lighting is dark and rich, with a light source, whether literal or figurative, often appearing over a character’s head:

And some of the outside shots have all the faded nostalgia of a 1950’s photograph:

Ah, yes: the cotton. Sinners is soaked in it. It’s in the background. It’s in the shots of sharecroppers at work. There’s even one scene where cottonwood floats through the trees, saturating the very air.

There are also what seem to be allusions to other films. At one point, the hillbillies/vampires sing “Wild Mountain Thyme,” which feels eerily like the “Siren Song” in O Brother, Where Art Thou? And there’s a scene that appears to be a pastiche of the scene in Once Upon a Time in the West where the radiant mail-order bride, abandoned at a train station, is attended only by a couple of Black porters.

But the heart of Sinners is the music. It’s what summons the demons, whom the brothers know must be confronted. Near the end of the movie, when Sammie is undergoing a dark baptism at the hands of Remmick, he smites him with his guitar. And perhaps the most iconic scene, which reminded me of the dream sequence in Black Panther where T’Challa meets the spirits of the ancestors, transcends the narrative to show dancers from different times and different places all celebrating together.

The scene is getting plenty of attention on the internet. Bill Bria at SlashFilm called it “2025’s Greatest Movie Scene (So Far),” and he writes,

As Coogler and cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw’s camera glides around the entire space, we see that Sammie has indeed pierced the veil, causing the musical ancestors and descendants of the primarily Black crowd to appear in the space. This means that everything from African tribal musicians to electric guitar players to old-school hip hop MCs to modern-day DJs is both enjoying and contributing to the performance. The presence of some Chinese-American friends of the owners means that some of their brethren are present, too, with some Xiqu performers milling about. As the performance escalates further, the old sawmill that the juke’s been built inside appears to burn away, something which presages the near future but also indicates how the music is transporting the people inside the building into another space, one of shared cultural harmony, literally and figuratively. It is an amazing scene that perfectly encapsulates the vast power of art itself.

To quote one of the characters at the end of the film, “For a few hours, we was free.”

However, it might be an injustice to Sinners to say that it’s about the power or art. This is a certain kind of art, for a certain community, existing in a certain place and time—an American one. Literature scholar Mathias Clasen has suggested that, unlike comedy, which is based on culture, horror is universal, pushing our “cognitive buttons.” And, yes, Sinners has those triggers: blood, violence, the terror that lies in the darkness just outside your window.

To really get the metaphorical horrors that permeate Sinners, though, you need to know the real horrors that birthed it.

Leave a comment