What dire offence from am’rous causes springs,

What mighty contests rise from trivial things.

–Alexander Pope

One of my colleagues currently has a student who claimed in class that the Civil War “was not about slavery.” That’s a popular argument with Lost Causers. But is it true?

It seems like a good time to revisit the (seemingly) trivial subject of prepositions.

According to the Online Etymological Dictionary, “about” comes from Old English “abutan,” which is a compound of another preposition, “on”– “in a position above and in contact with; in such a position as to be supported by”—and “utan,” meaning “outside.” And then, “By c. 1300 it had developed senses of “around, in a circular course, round and round; on every side, so as to surround; in every direction.”

So then, you have any number of instances outside of yet still in contact with and supported by a central core, like an atom, or the way a book can be said to be “about” one particular topic.

The Civil War was, indeed, “about” slavery. All the passions, all the grievances, and all the politics that led to the War have it at their core. Lincoln expressed this at the time, in his Second Inaugural Address–“These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war”—and in an 1862 reply to a religious group from Chicago, who were calling for him to issue an Emancipation Proclamation—”I admit that slavery is the root of the rebellion, or at least its sine qua non.” And Ulysses S. Grant, in the Conclusion of his Memoirs, writes, “The cause of the great War of the Rebellion against the United States will have to be attributed to slavery.” And, according to Sherman, in his own Memoirs, “That civil war, by reason of the existence of slavery, was apprehended by most of the leading statesmen of the half-century preceding its outbreak, is a matter of notoriety.”

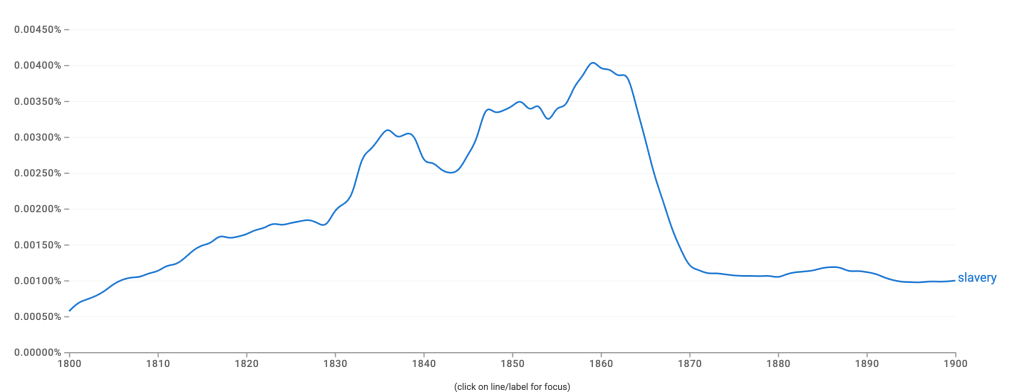

Sherman’s pronouncement is visibly reflected in this graph from Google’s nGram Viewer, showing the word “slavery” appearing with growing frequency in print from 1800 to the outbreak of the War, then dropping off precipitously.

(It should be noted that “slavery” declined but slavery didn’t—it just learned to call itself by other names.)

The Confederacy, itself, recognized the salience of slavery as a reason for secession. Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens, in his Cornerstone Speech of March 21, 1861, announced,

The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the “rock upon which the old Union would split.” He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact.

And Ta-Nehisi Coates, using yet another preposition in an article at The Atlantic titled, “What This Cruel War Was Over,” quotes leaders from Alabama, Florida, Texas, Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana explicitly and repeatedly saying that slavery was the reason for secession.

And in the North? Well, while most of the people weren’t abolitionists, they were growing increasingly indignant over policies forcing them to, not only tolerate, but protect slavery. Abraham Lincoln, in a speech at Cincinnati in 1859, told “the Kentuckians” in the audience:

What do you want more than anything else to make successful your views of slavery–to advance the outspread of it, and to secure and perpetuate the nationality of it? What do you want more than anything else? What is needed absolutely? What is indispensable to you? Why, if I may, be allowed to answer the question, it is to retain a hold upon the North, it is to retain support and strength from the free States…If you do not get this support and strength from the free States, you are in the minority, and you are beaten at once.

And, as Grant writes, in the Conclusion of his Memoirs,

Slavery was an institution that required unusual guarantees for its security wherever it existed; and in a country like ours where the larger portion of it was free territory inhabited by an intelligent and well-to-do population, the people would naturally have but little sympathy with demands upon them for its protection.

By the time the War started, the North had faced several impositions from the “slave power”: the Three-Fifths Compromise (1787), the Missouri Compromise (1820), the Fugitive Slave Act (1850), and the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854). The people must have been suffering from compromise fatigue.

The actual temper of the people can be seen during the case of Anthony Burns, an escaped slave who was captured and brought to trial in Boston in 1854. According to Albert J. Von Frank, in The Trials of Anthony Burns, when Burns was convicted and ordered sent back to Virginia by ship, almost the whole city turned out and Burns had to be led down to the wharf by a company of soldiers. “We went to bed apathetic,” wrote one observer, “and woke up stark, raving abolitionists.” Another observer, Martha Russell, wrote:

Did you ever feel every drop of blood in you boiling and seething, throbbing and burning, until it seemed you should suffocate? Did you ever set your teeth hard together to keep down the spirit that was urging you to do something to cool your indignation that good and wise people would call violence–treason? I felt that today.

“Little sympathy,” indeed! One wonders what would have happened had the South merely seceded, and not fired on Fort Sumter. We can’t know, but there’s nothing like some gunpowder to make a “boiling and seething” cauldron explode.

Let’s give the final word, to Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to John Holmes, on the Missouri Compromise, bringing Missouri into the union as a slave state:

[T]his momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. it is hushed indeed for the moment. but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. a geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once concieved and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper…as it is, we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.

Leave a comment